D Computer practical 4 - Analysis for Binary and Survival data

R practicalities - click here

There are many, many packages in R that implement methods for designing and analysing clinical trials (see a list at CRAN task view). We will look at some of these, and will also write our own code for some tasks. Remember that to install a package, you can do

If you have problems running R on your laptop, or on the university machines, the most foolproof way might be to use Github codespaces (thanks to Louis Aslett, who developed this for Data Science and Statistical Computing II). You may be familiar with this approach if you did Bayesian Computational Modelling III.

An advantage of this is that you can open the same codespace (the same instance of R) from any computer, so if you plan to work on things (for example your summative assignment, which will involve some R) from more than one computer, this might be ideal.

This requires you to have a github account (you can sign up for free here) and there is a short guide to creating a github account here.

In this practical we’ll focus on the analysis of binary and survival data. We’ll make use of several new packages. Installing them all now should hopefully prevent it from disrupting your flow! We’ll load them as we go along.

Notice that where there are code snippets that you want to copy directly, you can hover your cursor in the top right of the code box and a ‘copy’ icon will appear.

D.1 Binary outcome data

The dataset we’ll use to explore Binary outcome data is the respiratory dataset, from the package HSAUR. In this trial, patients across two centres were randomly assigned to receive treatment or placebo, and their respiratory status was recorded as either ‘poor’ or ‘good’. Measurements were recorded at months 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, but we will keep only month 0 (as a baseline) and month 4 (as a final outcome). We process the data below:

library(HSAUR)

data("respiratory")

# Keep only months 0 and 4

resp_04 = respiratory[respiratory$month %in% c(0,4),]

# Use month 4 data to form basis of overall dataset

resp_df = respiratory[respiratory$month %in% c(4),]

# add month 0 statusses in as baseline, and remove month column

resp_df$status0 = resp_04$status[resp_04$month==0]

resp_df = resp_df[ ,-6]For each patient, we have the following baseline covariates:

- sex

- age

- treatment centre (centre 1 or centre 2)

- symptom status (poor or good).

The outcome variable is whether the status of the patient’s symptoms are poor or good after four months of the trial. Note that unusually we do have the baseline observation of this quantity. We will build up through some of the models we studied in Chapter 6.

D.1.1 Confidence Intervals

Our first step will be to fit a Wilson confidence interval for the absolute risk difference, as we did in Section 6.2.1.3. Recall that the limits of a \(100(1-\alpha)\%\) CI for the ARD \(\pi_T - \pi_C\) are given by

\[ \left(p_T - p_C - \sqrt{\left(p_T-l_T\right)^2 + \left(u_C - p_C\right)^2},\; p_T - p_C + \sqrt{\left(u_T - p_T\right)^2 + \left(p_C - l_C\right)^2}\right), \] where \(p_X\) is the estimate of \(\pi_X\) (for group \(X\)), and \(\left(l_X,\,u_X\right)\) is the \(100\left(1-\alpha\right)\%\) CI for \(\pi_X\). The limits of the \(100\left(1-\alpha\right)\%\) Wilson CI for \(\pi_X\) are given by the roots of the equation (in \(\pi_X\))

\[ \left(p_X - \pi_X\right)^2 = z^2_{\frac{\alpha}{2}}\frac{\pi_X\left(1-\pi_X\right)}{n}. \]

Exercise D.1 Using only the final / month 4 outcomes, find the Wilson 95% CI for the ARD for the resp_df dataset we made above, treating a ‘good’ respiratory status as 1 and a ‘poor’ respiratory status as 0. Translate this into a confidence interval for the number needed to treat (NNT). Comment on the result.

Click for solution

Solution. The first thing we need to do is to find the limits of the individual CIs for groups C and T. To do this, we need the data estimates of \(p_C\) and \(p_T\).

rC = sum((resp_df$status == "good")&(resp_df$treatment == "placebo"))

nC = sum(resp_df$treatment == "placebo")

pC = rC / nC

rT = sum((resp_df$status == "good")&(resp_df$treatment == "treatment"))

nT = sum(resp_df$treatment == "treatment")

pT = rT / nTTo find the limits of the individual CIs, we need to rearrange the quadratic equation above into the form we’re used to

\[\left(1 + \frac{z^2}{n}\right)\pi^2 + \left(-2p-\frac{z^2}{n}\right)\pi + p^2 = 0.\] It is simple to define a function to solve quadratic equations in this form, for example

quad_fun = function(a,b,c){

disc = b^2 - 4*a*c

lower = (-b - sqrt(disc))/(2*a)

upper = (-b + sqrt(disc))/(2*a)

c(lower, upper)

}and we can now find the limits of each CI:

# Control group

lim_resp_C = quad_fun(

a = 1 + qnorm(0.975)^2/nC,

b = -2*pC - qnorm(0.975)^2/nC,

c = pC^2

)

lim_resp_C## [1] 0.3177270 0.5672199# Treatment group

lim_resp_T = quad_fun(

a = 1 + qnorm(0.975)^2/nT,

b = -2*pT - qnorm(0.975)^2/nT,

c = pT^2

)

lim_resp_T## [1] 0.4962747 0.7457662Notice that because \(p_C\) is quite close to 0.5, the Newcome interval for \(\pi_C\) is close to symmetric. The CI for \(\pi_T\) is more skewed.

Finally we can use these values to find the Wilson CI for the ARD:

# Make objects match notation

lC = lim_resp_C[1]

uC = lim_resp_C[2]

lT = lim_resp_T[1]

uT = lim_resp_T[2]

l_newc = pT - pC - sqrt((pT - lT)^2 + (uC - pC)^2)

u_newc = pT - pC + sqrt((uT - pT)^2 + (pC - lC)^2)

c(l_newc, u_newc)## [1] 0.005756246 0.358655200Finally we can use this to find a 95% CI for the NNT by finding the reciprocals of the limits of the CI for ARD:

## [1] 2.788193 173.724346This is a huge range and would make it difficult to make a clinical decision.

With the quantities we’ve found in exercise D.1 we can also find an approximate 95% CI for the risk ratio (see Section 6.2.2.1).

Exercise D.2 Find a 95% CI for the risk ratio \(\frac{\pi_T}{\pi_C}\) and comment on your result.

Click for solution

Solution. Recall that the limits of the \(100\left(1-\alpha\right)\%\) CI for the log of the risk ratio are given by

\[ \log\left(\frac{p_T}{p_C}\right) \pm z_{\frac{\alpha}{2}}\sqrt{\left(r_T^{-1} - n_T^{-1}\right) + \left(r_C^{-1} - n_C^{-1}\right)}. \]

Therefore for our respiratory data we have

# Find the estimated log OR and the distance to the limits of the CI

log_or_resp = log(pT/pC)

ci_diff = qnorm(0.975)*sqrt(1/rT - 1/nT + 1/rC - 1/nC)

# Calculate CI

ci_log_rr = c(log_or_resp - ci_diff, log_or_resp + ci_diff)

ci_log_rr## [1] 0.003626936 0.719476906To transform this into a CI for the RR itself, we use

## [1] 1.003634 2.053359This seems like a relatively narrow CI, but the fact that it comes so close to containing one (the ‘null value’ for the risk ratio) fits with the very large upper limit on the NNT / small lower limit on the ARD. Although this treatment appears significant, it may be that it has a very minimal effect in practice.

D.1.2 Logistic regression

We next looked at logistic regression as way to account for the baseline covariates. To fit a logistic regression in R we use the function glm. This fits all kinds of generalised linear models, and so we specify that we want a logistic regression by choosing family = binomial(link='logit').

The code is included in all examples in Sections 6.3 and 6.4, so if you aren’t sure how to do something they would be a good place to look.

Exercise D.3 Fit a logistic regression model to the resp_df data set, being careful to check for any issues with the data.

Click for solution

Solution. The first model we fit involves all covariates linearly:

model1 = glm(status ~ centre + treatment + sex + age + status0,

family = binomial(link='logit'), data=resp_df)

summary(model1)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = status ~ centre + treatment + sex + age + status0,

## family = binomial(link = "logit"), data = resp_df)

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -0.83921 0.67498 -1.243 0.213757

## centre2 1.27397 0.48546 2.624 0.008684 **

## treatmenttreatment 1.08498 0.47415 2.288 0.022122 *

## sexmale 0.33480 0.60171 0.556 0.577924

## age -0.02978 0.01805 -1.650 0.099035 .

## status0good 1.72562 0.47024 3.670 0.000243 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 153.44 on 110 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 119.34 on 105 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 131.34

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4and we can inspect the variance inflation factor to check for multicollinearity:

## centre treatment sex age status0

## 1.171418 1.120405 1.213698 1.194655 1.066666We can also try one with age squared, since the effect might not be linear (the age range is 11 to 68 which is quite a wide range). While we’re at it we’ll remove sex from the model since it appears to have no effect

model2 = glm(status ~ centre + treatment + I(age^2) + status0,

family = binomial(link='logit'), data=resp_df)

summary(model2)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = status ~ centre + treatment + I(age^2) + status0,

## family = binomial(link = "logit"), data = resp_df)

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -1.3668039 0.4973136 -2.748 0.005989 **

## centre2 1.2643943 0.4752453 2.661 0.007802 **

## treatmenttreatment 1.0236357 0.4559504 2.245 0.024764 *

## I(age^2) -0.0002696 0.0002305 -1.170 0.242143

## status0good 1.7046273 0.4618710 3.691 0.000224 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 153.44 on 110 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 120.80 on 106 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 130.8

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4Because the age range actually goes quite low, we could try a model with a log transform

model3 = glm(status ~ centre + treatment + I(log(age)) + status0,

family = binomial(link='logit'), data=resp_df)

summary(model3)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = status ~ centre + treatment + I(log(age)) + status0,

## family = binomial(link = "logit"), data = resp_df)

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 1.6939 1.8806 0.901 0.367733

## centre2 1.3303 0.4786 2.780 0.005440 **

## treatmenttreatment 1.0257 0.4605 2.227 0.025919 *

## I(log(age)) -1.0034 0.5570 -1.801 0.071638 .

## status0good 1.6769 0.4659 3.600 0.000319 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 153.44 on 110 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 118.74 on 106 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 128.74

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4## centre treatment I(log(age)) status0

## 1.131874 1.050760 1.111676 1.043080This is slightly better, so we’ll use it, but the model with age linear is pretty similar.

Exercise D.4 Perform some diagnostics on the model you fitted in Exercise D.3, focussing on the model’s ability to discriminate between outcomes, and also on how well the model calibrates to the observed data.

Click for solution

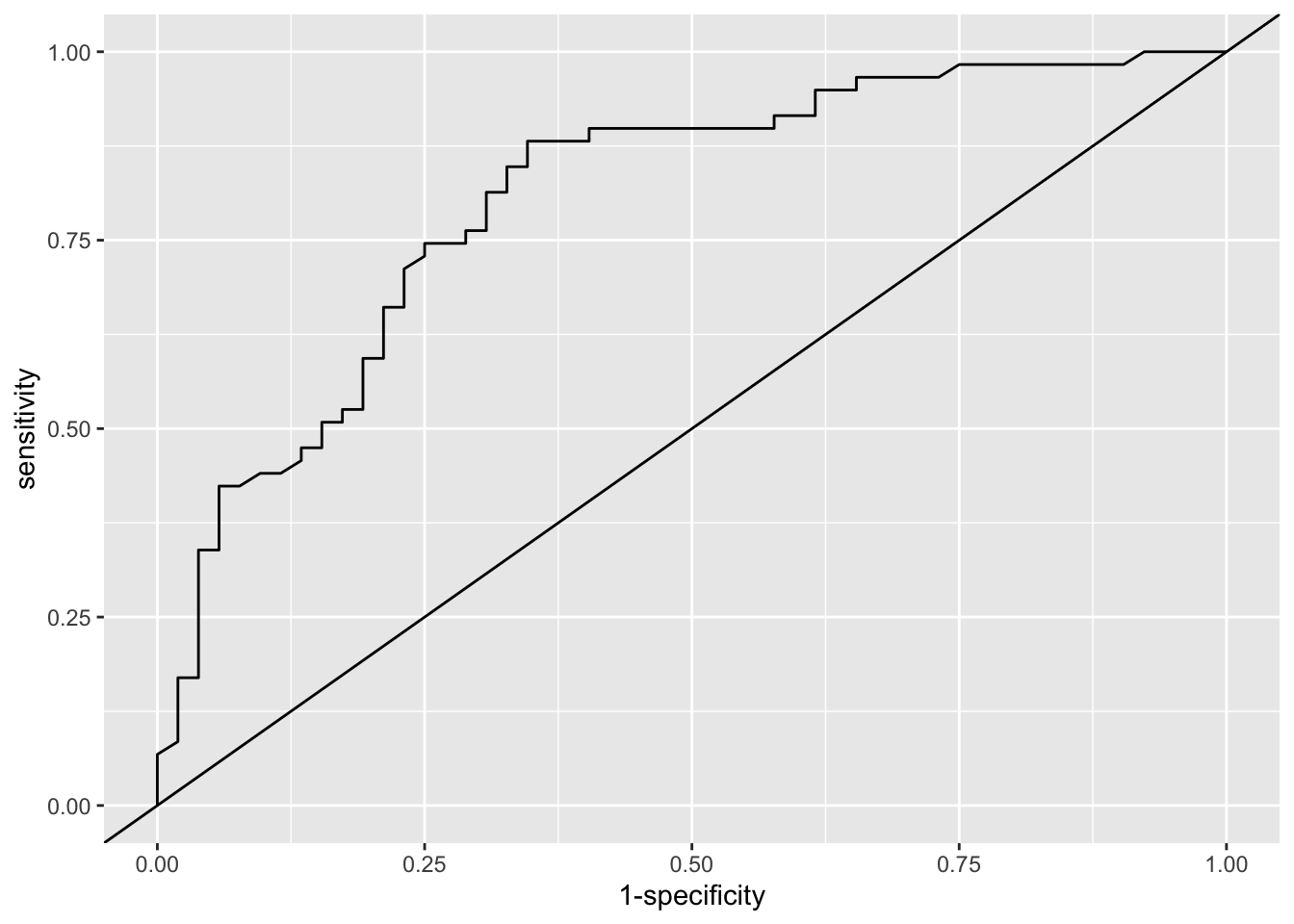

Solution. Firstly we’ll use ROC analysis to assess the model in terms of how well it discriminates the participants in terms of their respiratory status at 4 months.

library(pROC)

fit_resp = fitted(model3) # Fitted values from model3

out_resp = resp_df$status # outcome values (1 or 2)

roc_resp_df = data.frame(fit = fit_resp, out = out_resp)

roc_resp = roc(data=roc_resp_df, response = out, predictor=fit)

roc_resp##

## Call:

## roc.data.frame(data = roc_resp_df, response = out, predictor = fit)

##

## Data: fit in 52 controls (out poor) < 59 cases (out good).

## Area under the curve: 0.8054We can also plot the ROC curve

Next we’ll assess the model in terms of calibration.

## Group the observations into age groups (I've chosen 10 year bins)

resp_df$age10 = round(resp_df$age, -1)

# find mean status (minus 1 because factor levels are 1 and 2) and number of obs

# for each combination of factor/age group levels

resp_sum = resp_df %>%

group_by(age10, centre, treatment, status0) %>%

summarise(mean = mean(as.numeric(status))-1, n=length(age10), .groups="keep")

# Plot the observations, using facet_wrap to deal with two of the factors

obs_plot = ggplot(data=resp_sum, aes(x=age10, col=treatment)) +

geom_point(aes(y=mean, size=n), pch=16) +

theme_bw()+

facet_wrap(c("centre", "status0")) + theme(legend.position = "bottom")

## To include the estimate and SD from the model, we use the original dataset with continuous age,

# fit model 3 including an estimate of SE, and use geom_line and geom_ribbon to add the fitted model with 95% intervals

fit_resp = predict(model3, newdata=resp_df, se.fit=T, type="response")

resp_df$fit = fit_resp$fit

resp_df$fit_se = fit_resp$se.fit

obs_plot + geom_line(data=resp_df, aes(x=age, y=fit)) +

geom_ribbon(data=resp_df, aes(x=age, ymin = fit - 1.96*fit_se, ymax = fit + 1.96*fit_se, fill = treatment), alpha=0.3)

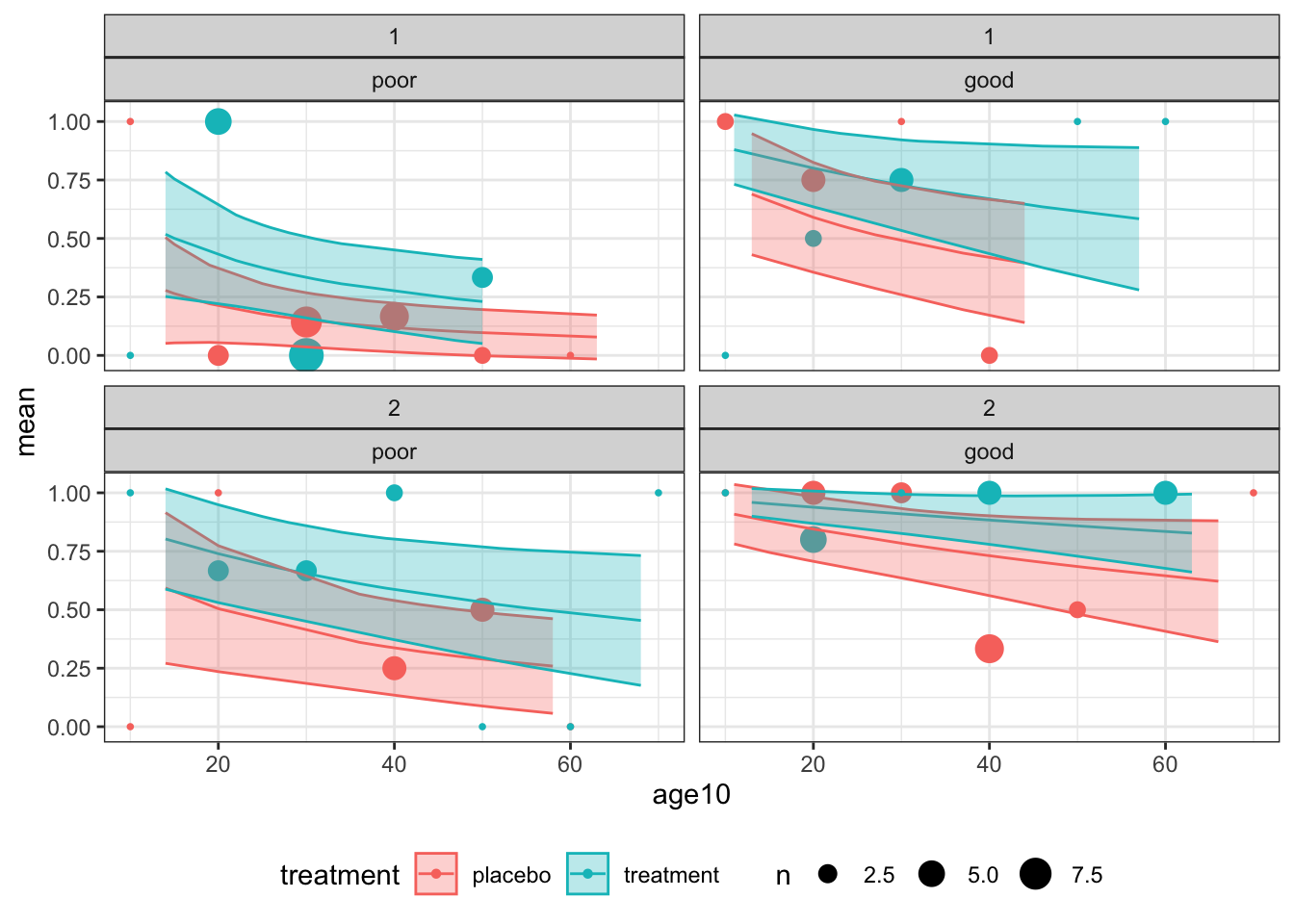

Figure D.1: Observations and fitted model for combinations of centre (1: top and 2: bottom) for baseline status (poor: left and good: right)

Overall, the model does not appear to be a great fit, but there is no systematic cause for concern.

These plots also give us an idea of the model’s fit for different categories of patient. For example, the probability of good respiratory symptoms at 4 months is much higher for a patient in the treatment group who had good symptoms at month zero, especially if they are young and belong to centre 2. The model’s output is much more bleak for a patient in group \(C\) at centre 1 who had poor symptoms at month zero.

Having performed some diagnostics, we can proceed to use our model to provide information about the effect of the treatment to improve respiratory symptoms.

Exercise D.5 Compute a 95% CI for the odd ratio for this trial, using the model you built in Exercise D.3.

Click for solution

Solution. We can find the details of the coefficients via

##

## Call:

## glm(formula = status ~ centre + treatment + I(log(age)) + status0,

## family = binomial(link = "logit"), data = resp_df)

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 1.6939 1.8806 0.901 0.367733

## centre2 1.3303 0.4786 2.780 0.005440 **

## treatmenttreatment 1.0257 0.4605 2.227 0.025919 *

## I(log(age)) -1.0034 0.5570 -1.801 0.071638 .

## status0good 1.6769 0.4659 3.600 0.000319 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 153.44 on 110 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 118.74 on 106 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 128.74

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4and find that the estimate of the log OR is 1.0257, with an SE of 0.4605, and therefore a 95% CI for the log OR is

est_logOR = summary(model3)$coefficients[3,1]

se_logOR = summary(model3)$coefficients[3,2]

logOR_CI = c(est_logOR - qnorm(0.975)*se_logOR, est_logOR + qnorm(0.975)*se_logOR)Finally we can use this to find a CI for the OR itself

## [1] 1.131069 6.877917This is further away from the null value (1 for the OR) than any of our previous confidence intervals, showing that including the baseline covariates has reduced our uncertainty in the treatment effect in a helpful way.

D.2 Analysis for Survival data

The packages we need for this section are survival, ggsurvfit and survminer, so load those now.

The first dataset we will use is aml - this dataset is from a trial investigating whether the standard course of chemotheraphy should be extended for some additional cycles (‘maintenance’) for patients with Acute Myelogenous Leukemia.

Exercise D.6 Look at the help file for the aml dataset and make sure you understand what each variable is doing.

R might ask which aml dataset you want - if it does, choose the one from the survival package.

Click for solution

Solution. The data set aml has three columns

time- survival or censoring time for each patient. This is the last time at which that patient was recorded.status- censoring status. By convention, this is 1 if a death is observed (ie. for complete data) and 0 for censored data (ie. the time in thetimecolumn was the last time that patient was seen, and they were still alive)x- maintenance chemotherapy given? This is the treatment variable

The first step is to combine the first two columns into a form we can use. We do this using the Surv function in the package survival, which creates a ‘survival object’ that we can then use in various other functions. This object contains the times and the information about which observations are censored.

To create a survival object from some dataset dataframe containing a time variable and a censoring status variable, the general form is

or if you prefer,

Exercise D.7 Use the Surv function now on the aml data. The output will contain some notation you probably haven’t seen before - can you work out what it means?

Click for solution

Solution. We create the survival object for aml by

## [1] 9 13 13+ 18 23 28+ 31 34 45+ 48 161+ 5 5 8 8 12 16+ 23

## [19] 27 30 33 43 45This is a vector of the time values, in the same order as in aml. You’ll notice that some have a ‘+’ attached. This denotes the censored observations (the notation reflects the fact that the true time of death/the event will be greater than this).

D.2.1 Fitting a survival curve

The next thing we probably want to do is to estimate the survival function and plot the survival curve. The first method we’ll use is the Kaplan-Meier estimator.

D.2.1.1 Kaplan-Meier

To fit a Kaplan-Meier survival curve, we use the function survfit, which is specified using a formula, much like lm or glm. To fit a Kaplan-Meier estimate with a data frame split by treatment effect, the general form is

We can then use summary to see the intermediary calculations at each step, and plot (for base plot) or ggsurvfit (from ggplot2 and ggsurvfit) to plot the curves.

Exercise D.8 Fit a Kaplan-Meier estimator to the aml data. View the table using summary. Plot the curves.

Click for solution

Solution. To fit the Kaplan-Meier estimator we use

We can then look at the summary table and plot the data by

## Call: survfit(formula = surv_aml ~ x, data = aml)

##

## x=Maintained

## time n.risk n.event survival std.err lower 95% CI upper 95% CI

## 9 11 1 0.909 0.0867 0.7541 1.000

## 13 10 1 0.818 0.1163 0.6192 1.000

## 18 8 1 0.716 0.1397 0.4884 1.000

## 23 7 1 0.614 0.1526 0.3769 0.999

## 31 5 1 0.491 0.1642 0.2549 0.946

## 34 4 1 0.368 0.1627 0.1549 0.875

## 48 2 1 0.184 0.1535 0.0359 0.944

##

## x=Nonmaintained

## time n.risk n.event survival std.err lower 95% CI upper 95% CI

## 5 12 2 0.8333 0.1076 0.6470 1.000

## 8 10 2 0.6667 0.1361 0.4468 0.995

## 12 8 1 0.5833 0.1423 0.3616 0.941

## 23 6 1 0.4861 0.1481 0.2675 0.883

## 27 5 1 0.3889 0.1470 0.1854 0.816

## 30 4 1 0.2917 0.1387 0.1148 0.741

## 33 3 1 0.1944 0.1219 0.0569 0.664

## 43 2 1 0.0972 0.0919 0.0153 0.620

## 45 1 1 0.0000 NaN NA NA

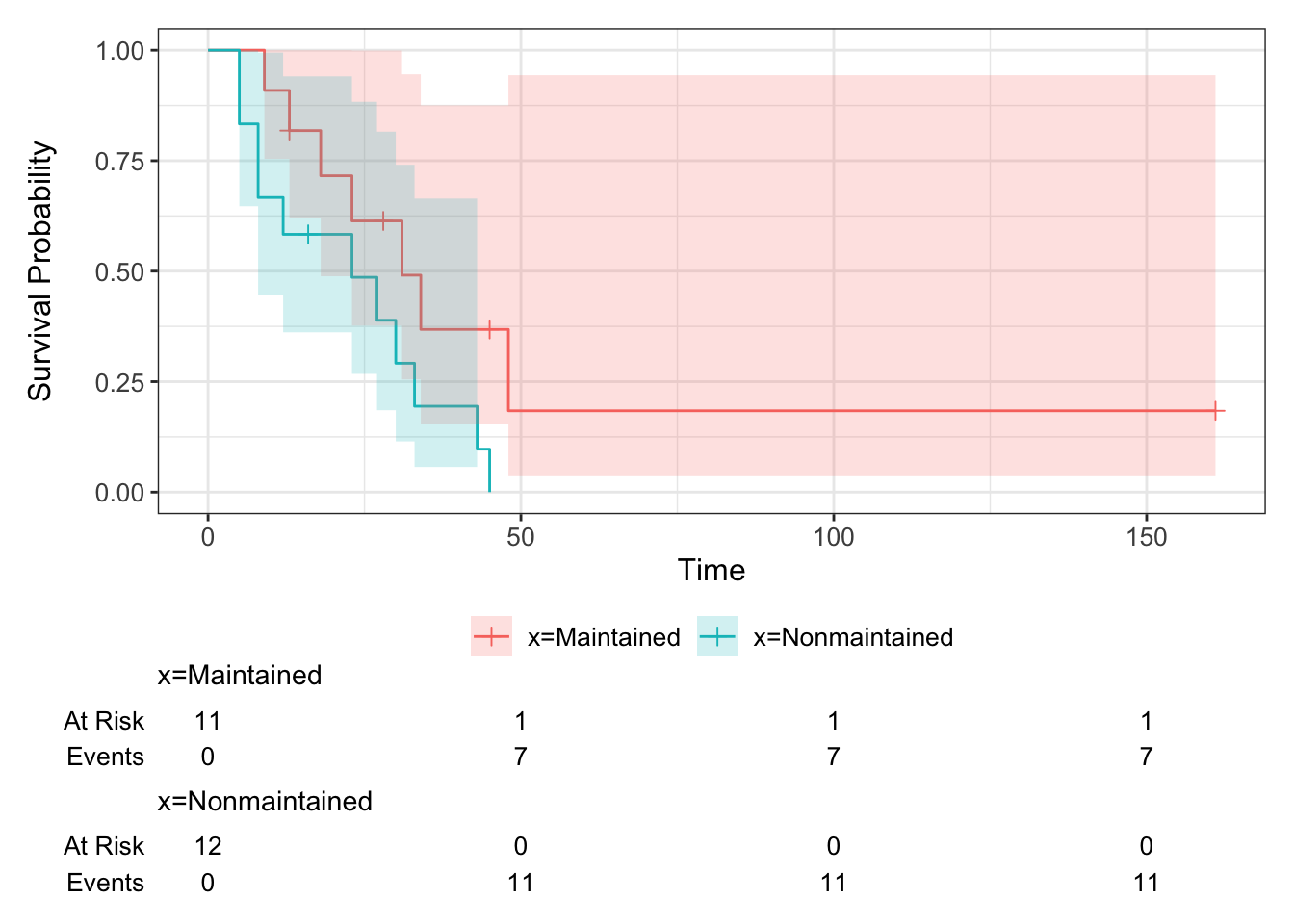

We can see from the table that the lower curve is the non-maintained arm - there is only one survivor of this group, and the data finish at \(t=45\).

The function add_risktable() adds information about the numbers at risk and numbers of events. The function add_confidence_interval() adds a confidence interval, and we see that with the aml data the uncertainty is huge.

D.2.1.2 Fitting an exponential distribution

To fit an exponential distribution, we need to estimate \(\hat\lambda_C\) and \(\hat\lambda_T\), using

\[\hat\lambda_X = \frac{m_X}{\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n_X} t_i} = \frac{m_X}{t^+_X}, \] where \(n_X\) is the number of observations \(t_1,\ldots,t_{n_X}\) in group \(X\), of which \(m_X\) are censored.

Exercise D.9 Fit an exponential distribution for each treatment group to the aml data and plot the resulting estimated survival curves, along with the Kaplan Meier estimators from Exercise D.8 (for comparison).

Click for solution

Solution. To calculate \(\hat\lambda_C\) and \(\hat\lambda_T\) we need to find \(m_C,\;\,m_T\;,t^+_C\) and \(t^+_T\).

mC_aml = sum((aml$status==1)&(aml$x=="Nonmaintained"))

mT_aml = sum((aml$status==1)&(aml$x=="Maintained"))

tsum_aml_C = sum(aml$time[aml$x=="Nonmaintained"])

tsum_aml_T = sum(aml$time[aml$x=="Maintained"])

lamhat_aml_C = mC_aml / tsum_aml_C

lamhat_aml_T = mT_aml / tsum_aml_TWe can then plot the Survival curves using geom_function

# Define survival function for exponential density

exp_st = function(t, lambda){exp(-lambda*t)}

km_aml %>% ggsurvfit() + ylim(0,1) + theme_bw() +

add_censor_mark() +

geom_function(fun=exp_st, args=list(lambda = lamhat_aml_C), col="darkturquoise") +

geom_function(fun=exp_st, args=list(lambda = lamhat_aml_T), col="red")

D.2.2 Comparing survival curves

Having found the MLEs for the aml dataset, assuming an exponential distribution, we can now immediately conduct a likelihood ratio test.

D.2.2.1 Likelihood ratio test

Recall that our test statistic (which we found in Section 8.1) is

\[ \lambda_{LR} = 2\left(m_C\log\left(\frac{m_C}{t^+_C}\right) + m_T\log\left(\frac{m_T}{t^+_T}\right) - m\log\left(\frac{m}{t^+}\right)\right),\]

which we then refer to a \(\chi^2_1\) distribution.

Exercise D.10 Conduct a likelihood ratio test for the aml data, with the null hypothesis that the survival curves are the same for both treatment groups. Before you calculate the answer, think about what you expect to see.

Click for solution

Solution. We already have the \(m_X\) and \(t^+_X\) from Exercise D.9, and we can easily find \(t^+\) and \(m\) from these.

and we can use these to compute \(\lambda_{LR}\):

LRstat_aml = 2*(mC_aml*log(mC_aml/tsum_aml_C) + mT_aml*log(mT_aml/tsum_aml_T) - m_aml*log(m_aml/tsum_aml))

LRstat_aml## [1] 4.061349Finally, we refer this to \(\chi^2_1\)

## [1] 0.04387544We find that we have just enough evidence to reject \(H_0\) at the 95% level.

D.2.2.2 Log-rank test

Because our computer practicals are early in the week we haven’t covered this material yet in lectures. So, it might be sensible to return to it at a later date, and instead to continue to the extension question if you still have time in the session.

The log-rank test is most easily found using the function survdiff. This function has an argument rho that controls the type of test. If we set rho=0 then it performs a log-rank test.

The general form is similar to survfit:

Exercise D.11 Use survdiff to do a log rank test on the aml data. Do you expect the results to be similar to your results from Exercise D.10?

Click for solution

Solution. To conduct a log rank test we use

## Call:

## survdiff(formula = surv_aml ~ x, data = aml, rho = 0)

##

## N Observed Expected (O-E)^2/E (O-E)^2/V

## x=Maintained 11 7 10.69 1.27 3.4

## x=Nonmaintained 12 11 7.31 1.86 3.4

##

## Chisq= 3.4 on 1 degrees of freedom, p= 0.07This is not that close to the result of the likelihood ratio test, probably reflecting the less-than-perfect fit of the exponential survival curve.

D.2.2.3 Cox regression

Finally, we will fit the Cox regression model. This is done using the function coxph in the package survival. Look at the help file and the examples in Section 8.3.2 to understand how to use this function.

Exercise D.12 Fit a Cox proportional hazards model to the data. Do you think this is an appropriate model to use? How influential is the treatment?

Click for solution

Solution. In the aml dataset there are no baseline covariates, so our only dependent variable is the treatment group variable x.

## Call:

## coxph(formula = Surv(time, status) ~ x, data = aml)

##

## coef exp(coef) se(coef) z p

## xNonmaintained 0.9155 2.4981 0.5119 1.788 0.0737

##

## Likelihood ratio test=3.38 on 1 df, p=0.06581

## n= 23, number of events= 18We’ve already seen that the survival curves don’t cross, so we can be reasonably comfortable fitting this model. To see how the model performs, we can use the summary function:

## Call:

## coxph(formula = Surv(time, status) ~ x, data = aml)

##

## n= 23, number of events= 18

##

## coef exp(coef) se(coef) z Pr(>|z|)

## xNonmaintained 0.9155 2.4981 0.5119 1.788 0.0737 .

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## exp(coef) exp(-coef) lower .95 upper .95

## xNonmaintained 2.498 0.4003 0.9159 6.813

##

## Concordance= 0.619 (se = 0.063 )

## Likelihood ratio test= 3.38 on 1 df, p=0.07

## Wald test = 3.2 on 1 df, p=0.07

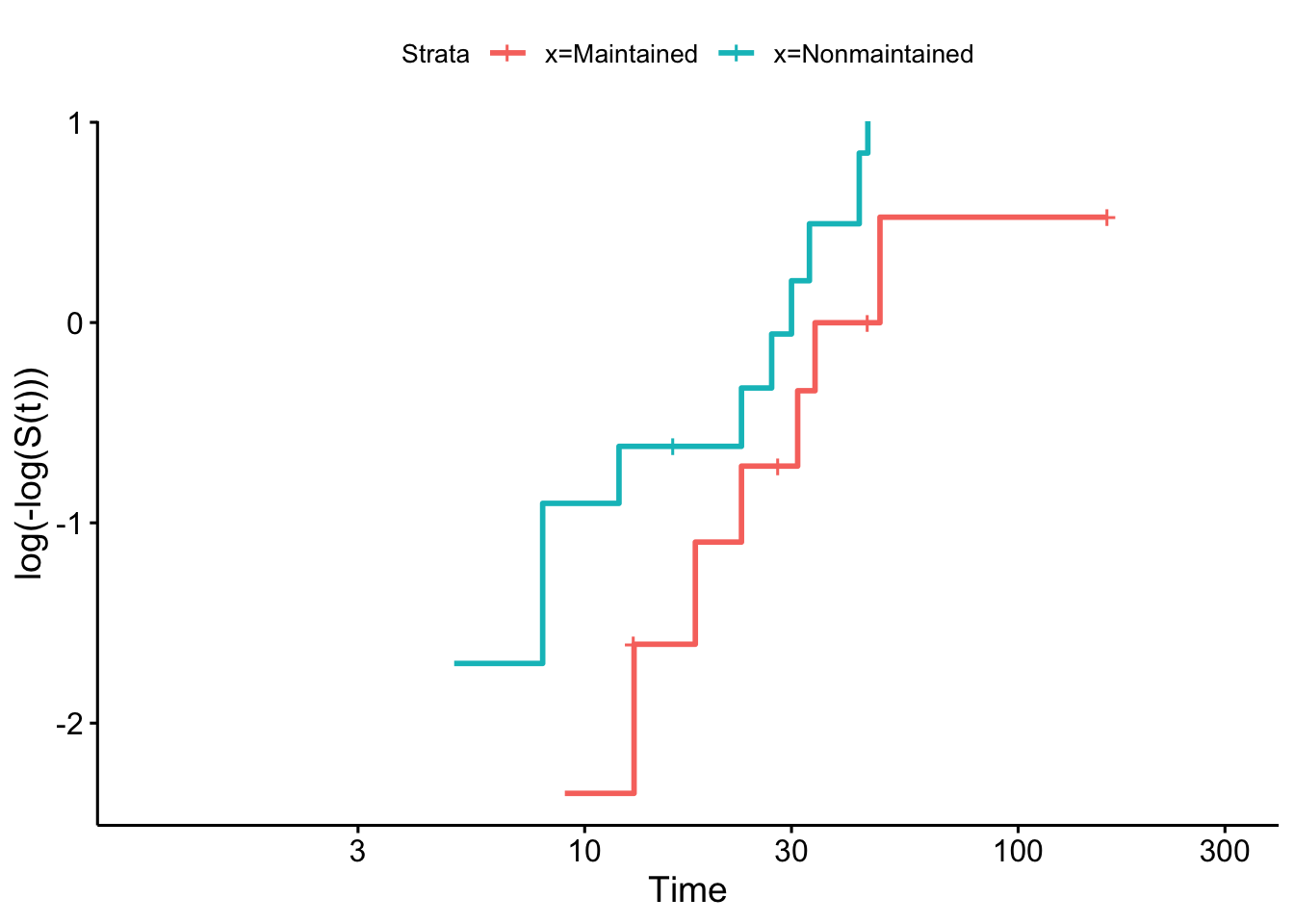

## Score (logrank) test = 3.42 on 1 df, p=0.06To check this more carefully we can use the log-log plot

and we see that the curves are close to parallel.

Although the coefficient of x isn’t quite significant at the 0.05 level, it appears there is reasonable evidence that the treatment has an effect (though probably not enough to make a clinical decision).

Exercise D.13 The dataset colon, also from the survival package, contains data from a trial of colon cancer patients, comparing three treatments: observation (obs), levamisole (Lev) and levamisole + 5-FU (Lev+5FU). To simplify things, we will restrict the data to those patients on Obs or Lev+5FU. The main report of this trial is Moertel et al. (1990).

colondf = colon[colon$rx!="Lev",]

colondf$rx = as.factor(as.character(colondf$rx)) # Removes Lev factor levelFor this data

- Look at the help file and make sure you understand what the columns mean

- Fit Kaplan-Meier estimators to the survival curves for the two groups.

- Perform some tests to see whether the treatment has a significant effect on the outcome. What do you find?

Click for solution

Solution. From the help file we see that rx is the treatment group, stop is the time variable, status gives the censoring status.

## 'data.frame': 1238 obs. of 16 variables:

## $ id : num 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 ...

## $ study : num 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ rx : Factor w/ 2 levels "Lev+5FU","Obs": 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 ...

## $ sex : num 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 ...

## $ age : num 43 43 63 63 71 71 66 66 69 69 ...

## $ obstruct: num 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 ...

## $ perfor : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ adhere : num 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ nodes : num 5 5 1 1 7 7 6 6 22 22 ...

## $ status : num 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ differ : num 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 ...

## $ extent : num 3 3 3 3 2 2 3 3 3 3 ...

## $ surg : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ node4 : num 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ time : num 1521 968 3087 3087 963 ...

## $ etype : num 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 ...We can therefore fit (and plot) the Kaplan-Meier estimator split by treatment group.

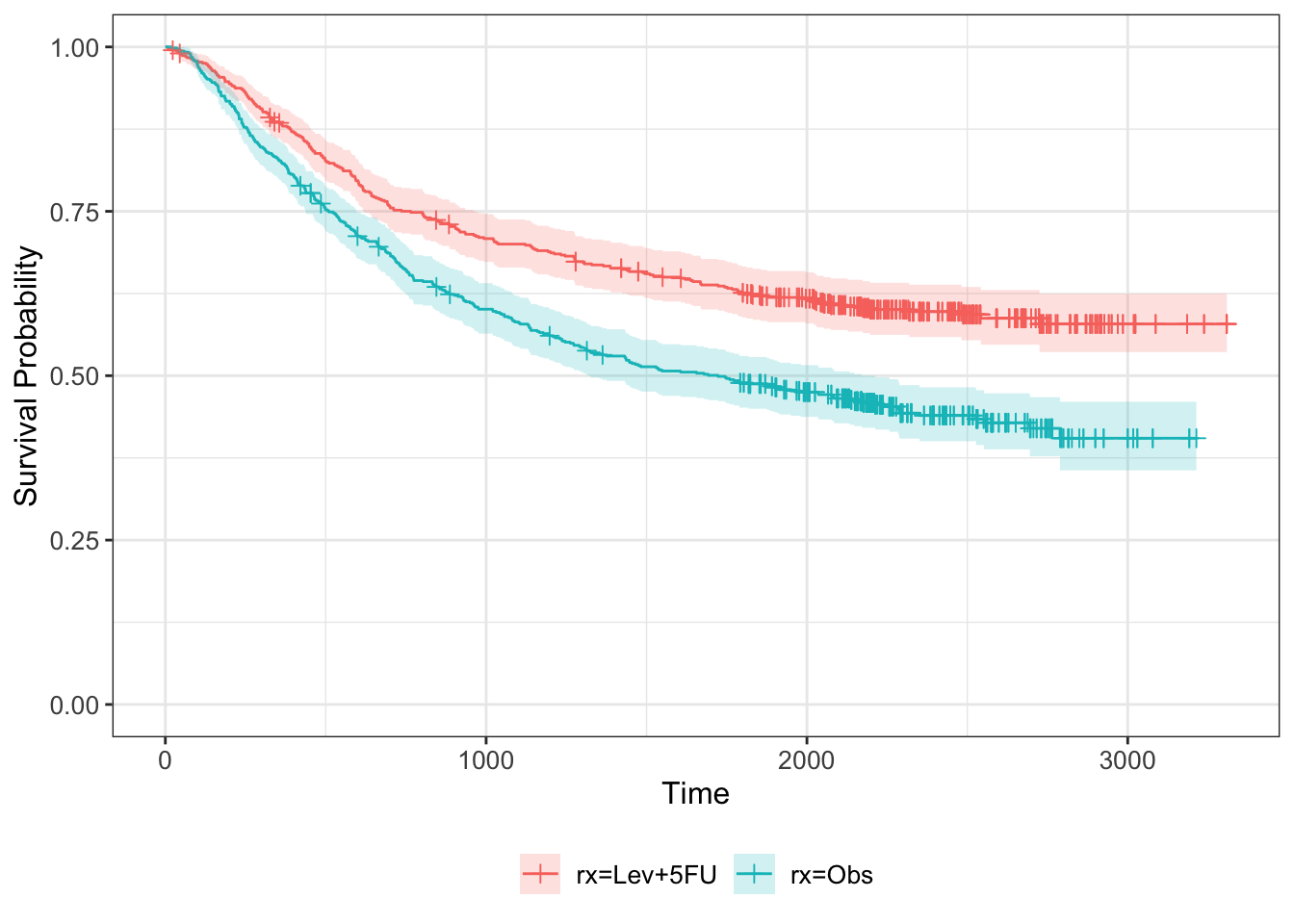

km_colon = survfit(Surv(time, status) ~ rx, data=colondf)

km_colon %>% ggsurvfit + ylim(0,1) +

add_censor_mark() +

add_confidence_interval()

Next we can find the MLE for each treatment group

mC_colon = sum((colondf$status==1)&(colondf$rx=="Obs"))

mT_colon = sum((colondf$status==1)&(colondf$rx=="Lev+5FU"))

tsum_colon_C = sum(colondf$time[colondf$rx=="Obs"])

tsum_colon_T = sum(colondf$time[colondf$rx=="Lev+5FU"])

lamhat_colon_C = mC_colon / tsum_colon_C

lamhat_colon_T = mT_colon / tsum_colon_TWe can then plot the Survival curves using geom_function

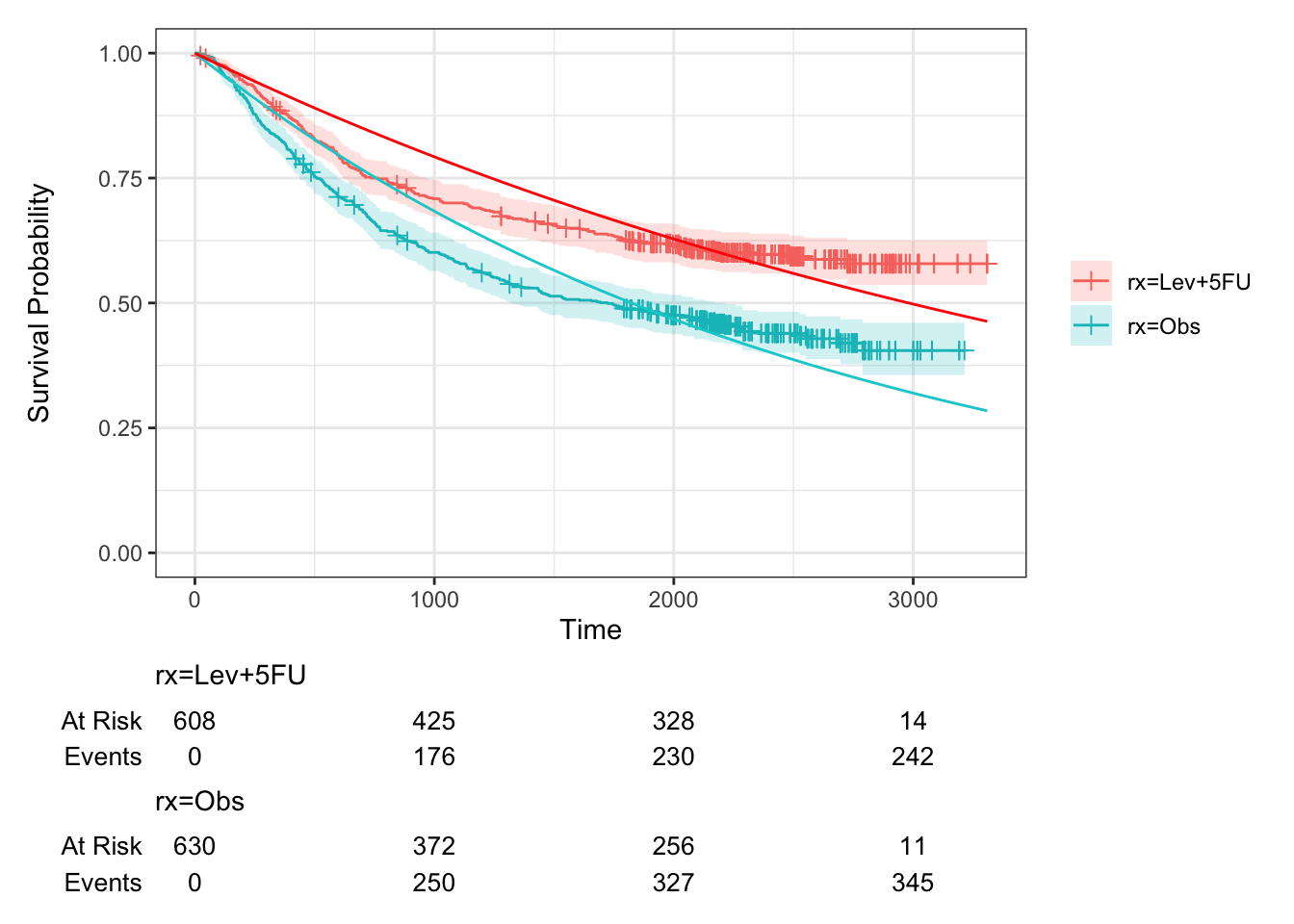

# Define survival function for exponential density

km_colon %>% ggsurvfit() +

add_censor_mark() +

add_risktable() +

add_confidence_interval() +

ylim(0,1) + theme_bw() +

geom_function(fun=exp_st, args=list(lambda = lamhat_colon_C), col="darkturquoise") +

geom_function(fun=exp_st, args=list(lambda = lamhat_colon_T), col="red")

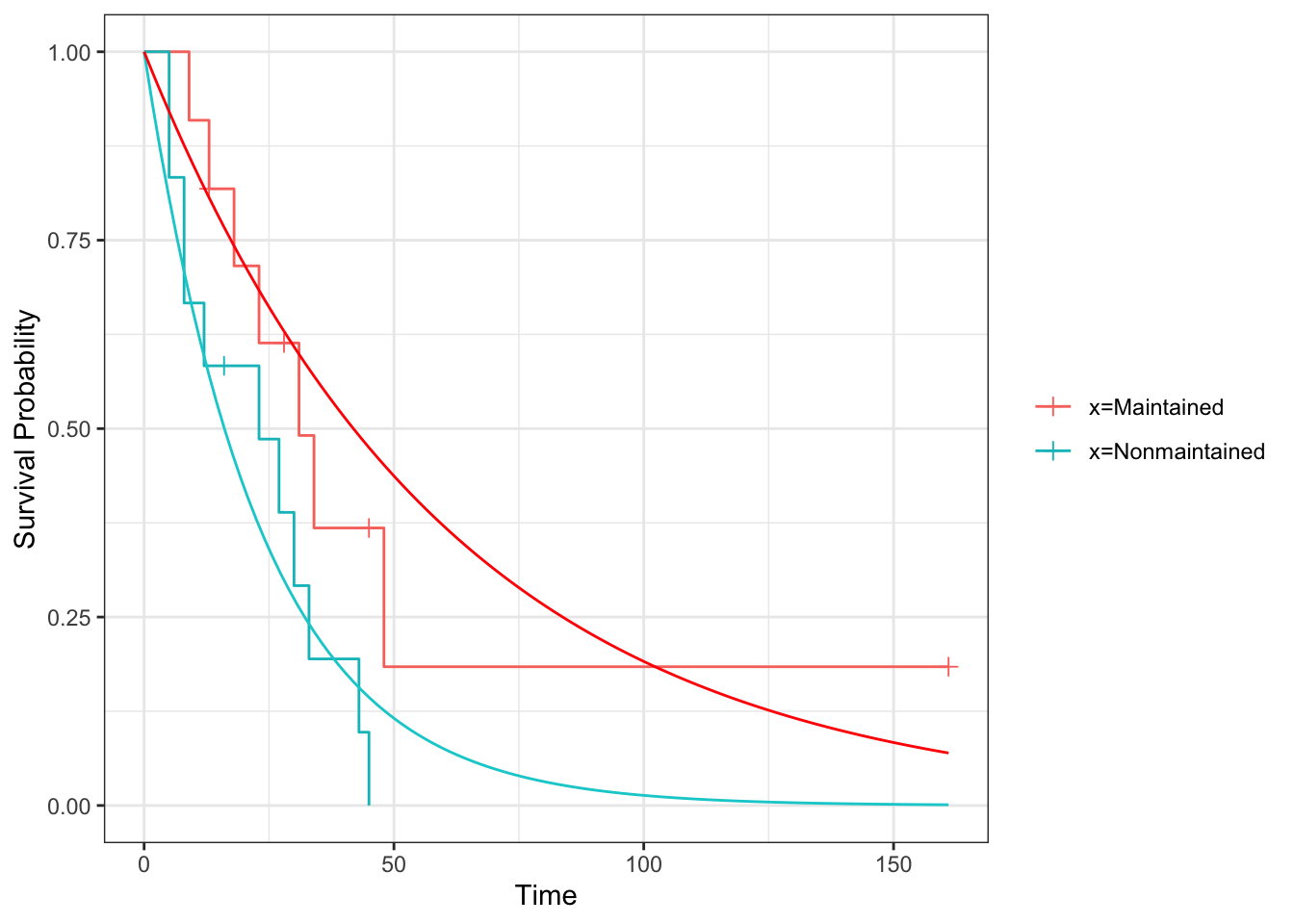

Figure D.2: Survival curves for groups C and T in colon study, fitted assuming an exponential distribution. Kaplan-Meier estimates also shown.

We see that this fit is quite poor.

and we can use these to compute \(\lambda_{LR}\):

LRstat_colon = 2*(mC_colon*log(mC_colon/tsum_colon_C) + mT_colon*log(mT_colon/tsum_colon_T) - m_colon*log(m_colon/tsum_colon))

LRstat_colon## [1] 35.0111Finally, we refer this to \(\chi^2_1\)

## [1] 3.278309e-09Highly significant, but because of the very poor fit in Figure D.2 not especially trustworthy.

Next, we can perform a log-rank test:

## Call:

## survdiff(formula = Surv(time, status) ~ rx, data = colondf, rho = 0)

##

## N Observed Expected (O-E)^2/E (O-E)^2/V

## rx=Lev+5FU 608 242 306 13.5 28.2

## rx=Obs 630 345 281 14.7 28.2

##

## Chisq= 28.2 on 1 degrees of freedom, p= 1e-07We see that the test statistic, although still very significant, is much lower than for the likelihood ratio test.

Finally, we fit a Cox regression model. In the first instance we can do this with just the treatment group as a covariate:

## Call:

## coxph(formula = Surv(time, status) ~ rx, data = colondf)

##

## coef exp(coef) se(coef) z p

## rxObs 0.44213 1.55602 0.08394 5.267 1.38e-07

##

## Likelihood ratio test=28.25 on 1 df, p=1.068e-07

## n= 1238, number of events= 587But we can also include other baseline covariates

## Call:

## coxph(formula = Surv(time, status) ~ rx + sex + age + obstruct +

## nodes, data = colondf)

##

## coef exp(coef) se(coef) z p

## rxObs 0.470039 1.600056 0.085522 5.496 3.88e-08

## sex -0.155126 0.856308 0.083835 -1.850 0.0643

## age -0.002940 0.997064 0.003400 -0.865 0.3872

## obstruct 0.072027 1.074685 0.105813 0.681 0.4961

## nodes 0.104607 1.110274 0.008493 12.317 < 2e-16

##

## Likelihood ratio test=146 on 5 df, p=< 2.2e-16

## n= 1214, number of events= 574

## (24 observations deleted due to missingness)and we see that as well as the treatment arm, the number of lymph nodes with detectable cancer (given by nodes) is highly significant, and sex is also fairly significant.

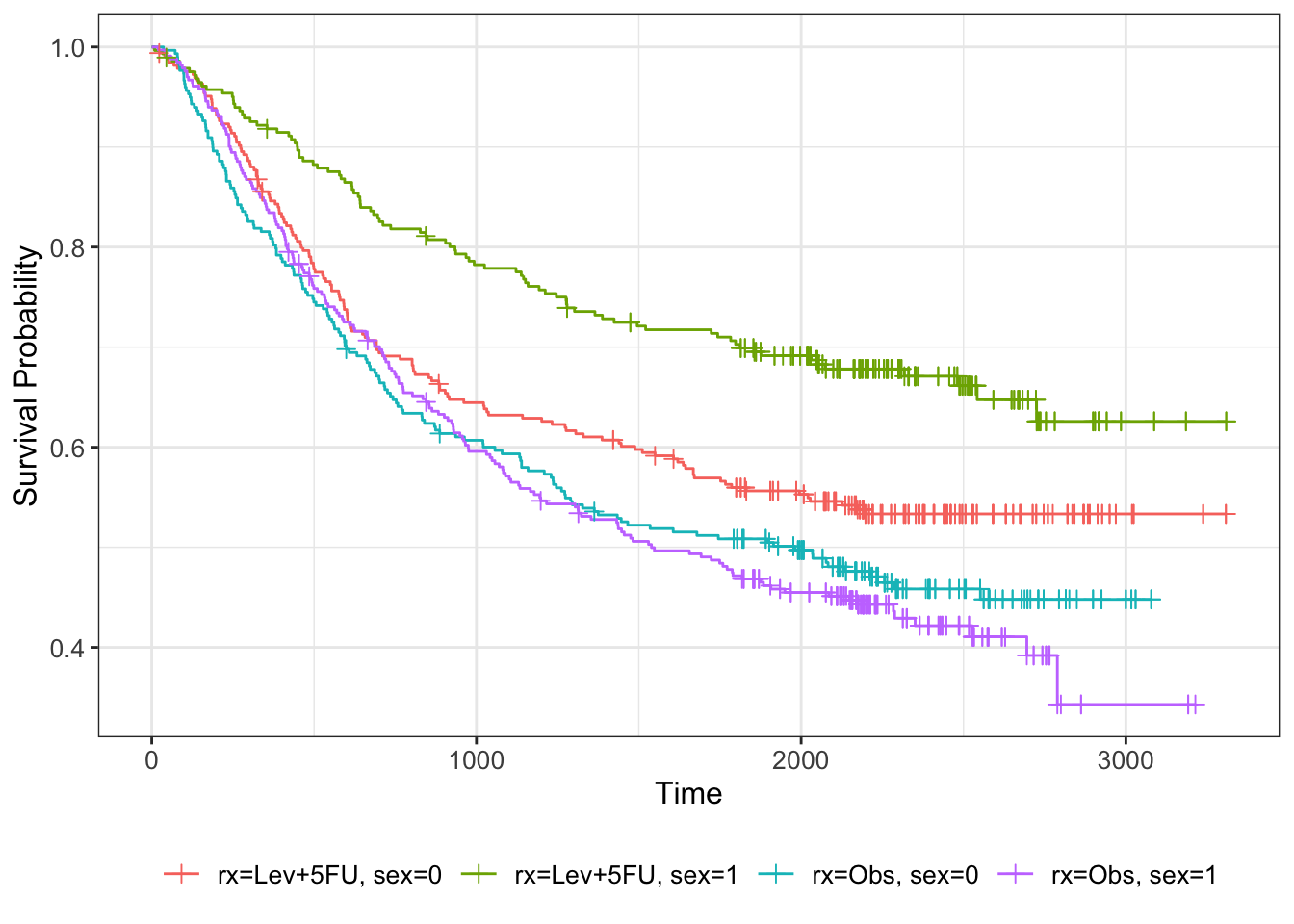

We can visualise this by further subsetting the Kaplan-Meier estimator

km_colon_bl = survfit(Surv(time, status) ~ rx + sex, data=colondf)

km_colon_bl %>% ggsurvfit() +

add_censor_mark()

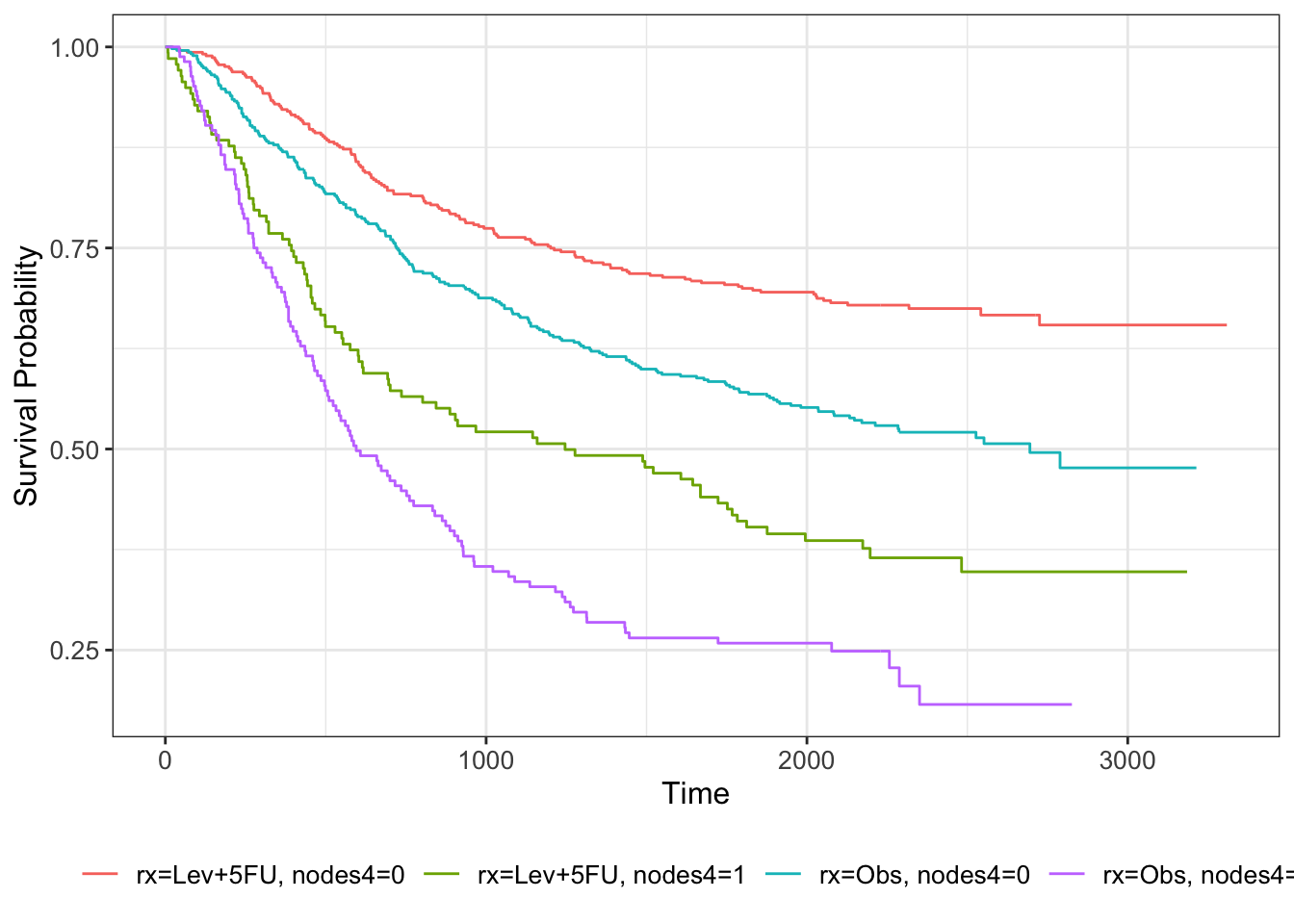

nodes is a numeric output, so one way to get a visual impression of its effect on the survival curve we can bin it. For example, we can choose \(\texttt{nodes}\leq 4\) and \(\texttt{nodes}>4\).

colondf$nodes4 = sapply(1:nrow(colondf), function(i){ifelse(colondf$nodes[i]>4, 1, 0)})

km_colon_bl = survfit(Surv(time, status) ~ rx + nodes4, data=colondf)

km_colon_bl %>% ggsurvfit()

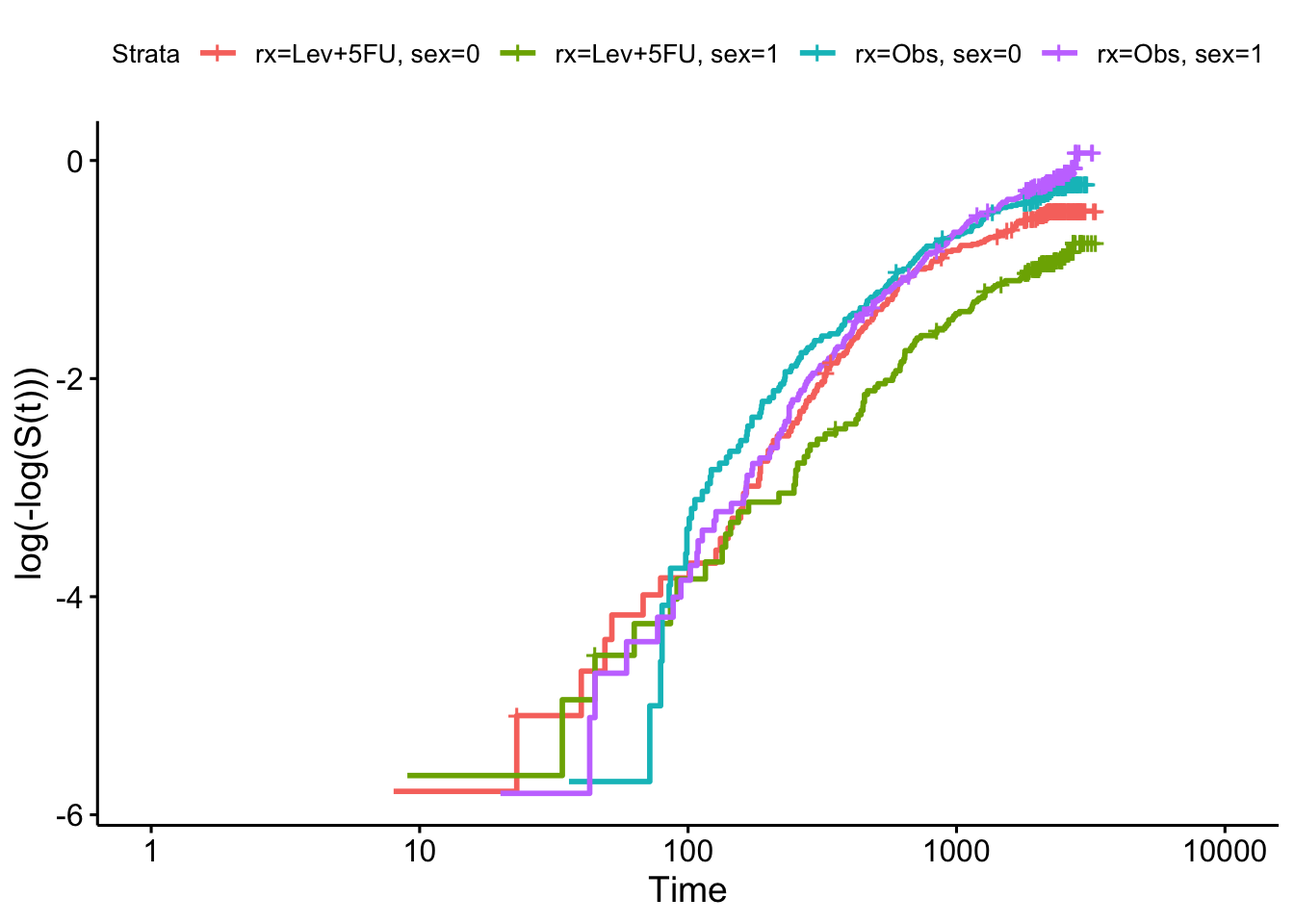

To check our model more carefully we can use the log-log plot for the categorical variables:

km_colon = survfit(Surv(time, status) ~ rx + sex, data=colondf)

ggsurvplot(km_colon, fun = "cloglog")

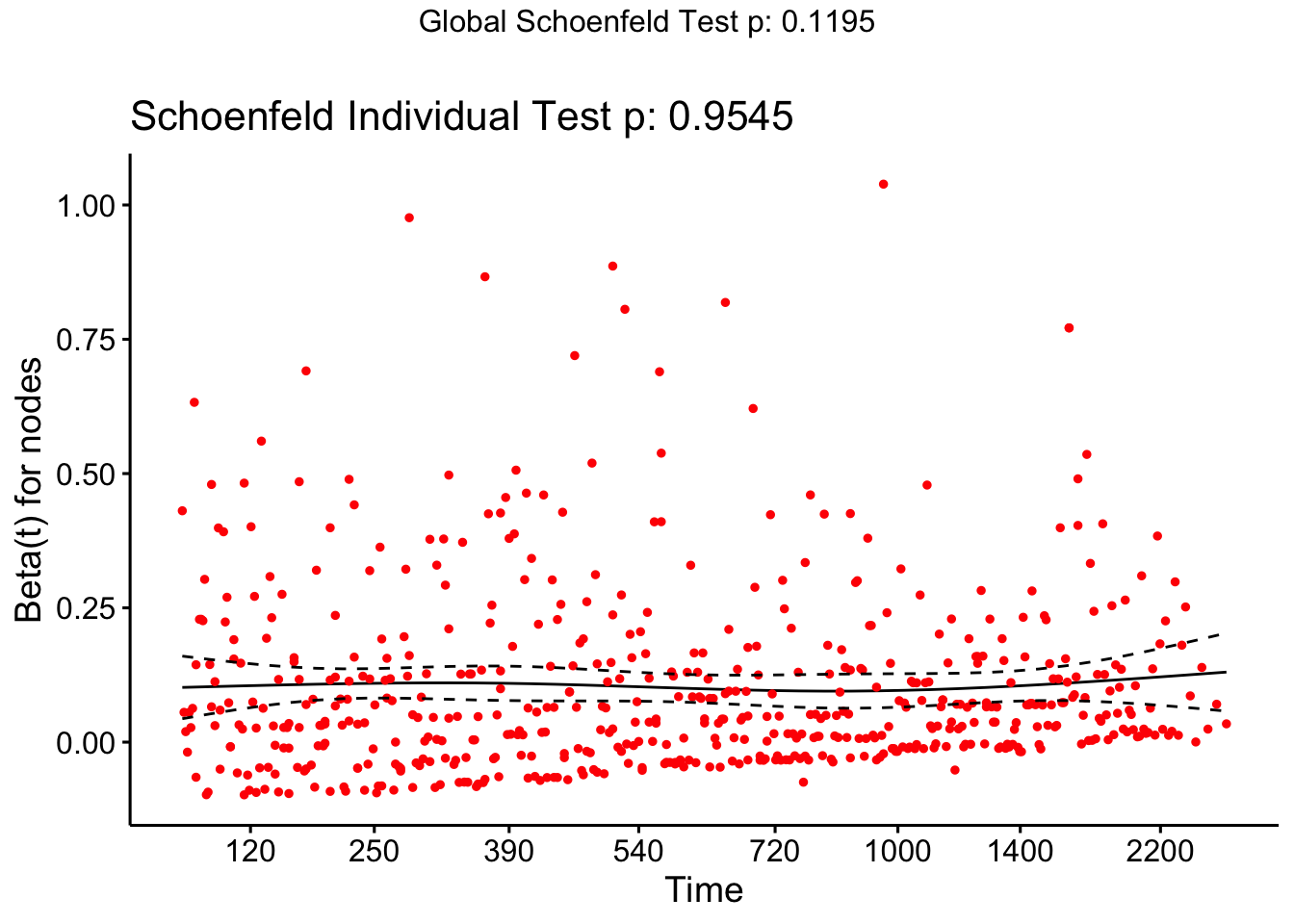

and the Schoenfeld residuals for the continuous residuals (after removing the insignificant variables):

cox_colon = coxph(formula = Surv(time, status)~rx + sex + nodes, data=colondf)

ggcoxzph(cox.zph(cox_colon), var = "nodes")

and we see that there is insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis (of proportional hazards).

D.3 Extension problem: Sample size by simulation (part II)

If you have time, you could now combine the work we’ve done in this practical and the previous one to implement power simulation for a binary outcome trial.

If you’ve found the above fairly simple, this will be a good exercise to stretch your muscles. If not, then please still give it some thought, but feel free to look at the solution to see how the method applied to another approach.

Before starting, look back at Practical 3 and the steps to the simulation method and consider what you’ve to do to complete the exercise.

Exercise D.14 Use simulation to find the appropriate size for a trial with a binary primary outcome variable. You can assume that the proportion of ‘successes’ in the control group is 0.65, and that the least clinically significant proportion we’d like to be able to detect is a treatment group proportion of 0.8. The trial should have a significance level of \(\alpha=0.05\) and a power of \(1-\beta = 0.8\).

Click for solution

Solution. The steps within each simulation are:

- Simulate data using

rbinom - Run some analysis method on that simulated data

- Record whether \(H_0\) was rejected

In the code below I’ve used the simplest type of analysis, a \(t\)-test on the absolute risk difference, but you could use any of the methods we’ve covered.

binom_sim = function(

nsim, # Number of simulations

N, # Number of participants in each arm

piC, # Assumed proportion in control group

piT # minimum detectably different proportion in treatment group

){

H0_reject_vec = rep(NA, nsim) # to store 1 if H0 rejected, 0 if fail to reject H0

for (i in 1:nsim){

rC = rbinom(n=1, size=N, prob=piC) # generate numbers of successes

rT = rbinom(n=1, size=N, prob=piT)

pC = rC/N # Find estimates of proportions

pT = rT/N

p_pooled = (rC+rT)/(2*N)

z_stat = (pT - pC) / (sqrt(p_pooled*(1-p_pooled)*(1/N + 1/N)))

p_val = 2*(1-pnorm(z_stat, mean=0, sd=1))

H0_reject_vec[i] = ifelse(p_val<0.05, 1, 0)

}

power.est = mean(H0_reject_vec)

power.est

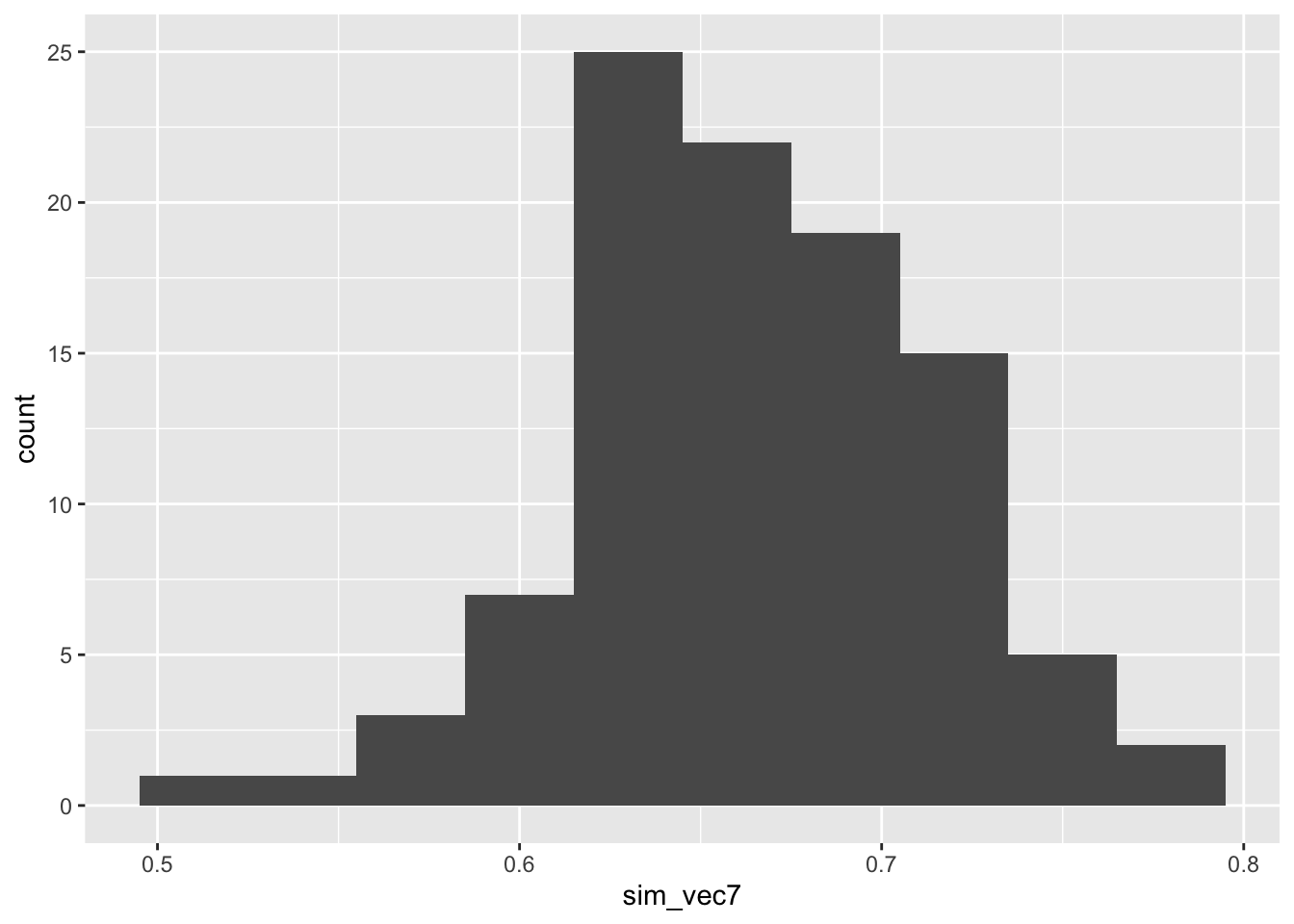

}Let’s now try this for \(N=100\), as a base point

sim_vec7 = rep(NA, 100)

for (i in 1:100){

sim_vec7[i] = binom_sim(nsim=100, N=100, piC=0.65, piT=0.8)

}

ggplot(mapping = aes(sim_vec7)) + geom_histogram(bins=10)

This is clearly too low so we can try a higher number - let’s say \(N=150\)

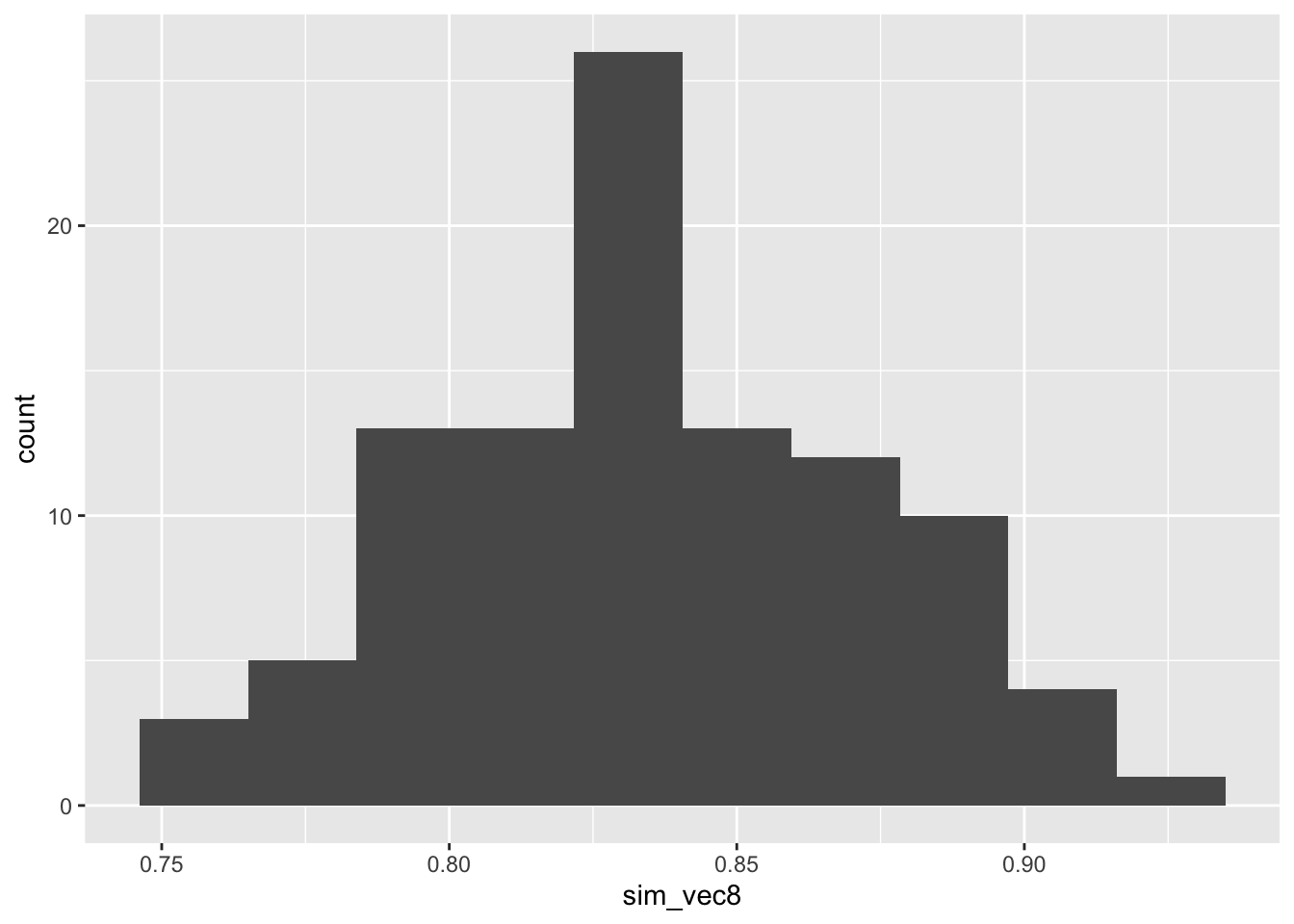

sim_vec8 = rep(NA, 100)

for (i in 1:100){

sim_vec8[i] = binom_sim(nsim=100, N=150, piC=0.65, piT=0.8)

}

ggplot(mapping = aes(sim_vec8)) + geom_histogram(bins=10)

This appears to be much closer - one could now finesse \(N\) to fit some criteria on the proportion of simulations achieving the desired power.

There are of course lots of ways we could refine and extend this, many of them similar to what we discussed in Section C, for example:

- Running more simulations (100 is really not enough, but was chosen so that the file would compile - feel free to increase it)

- Incorporating a better sampling scheme than SRS

- Improving the drop-out / censoring modelling

- Allowing the probability to vary in the data generation (this would be known as a sensitivity analysis).